Forward, Chapters 1 & 2 | The Events of March 19th

The Mayor’s Commission on Conditions in Harlem consisted of ten high-profile New Yorkers who lived and worked in Harlem or who had backgrounds in the matters to be reviewed.

- Eunice Hunton Carter, Secretary; the first African-American woman to work as a prosecutor for the Manhattan District Attorney

- Countee Cullen, poet, playwright and novelist, part of the Harlem Renaissance

- Hubert T. Delaney, New York City Commissioner of Taxes and Assessments

- Morris Ernst, prominent attorney, and co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

- John C. Grimley, former hospital director and commanding officer of the 369th Infantry

- Arthur Garfield Hays, founding member and general counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

- Reverend W.R. McCann, Roman Catholic pastor of St. Charles Borromeo Church

- A. Philip Randolph, prominent labor leader and head of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

- Charles Roberts, Chair First Black person elected to the New York City Board of Alderman

- John W. Robinson, prominent minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church who represented the Interdenominational Ministers Alliance

- William J. Schieffelin, social reformer and trustee of Tuskegee Institute

- Charles E. Toney, Municipal Judge and NAACP Board Member

- Oswald Garrison Villard, publisher of the Evening Post and one of the NAACPs founders

Chapter 2

The Commission established six subcommittees: Crime and the Police, Education, Housing, Discrimination in Employment, Health and Hospitalization and Relief. The subcommittees held hearings, gathered personal testimony, analyzed budgets, and tracked employment statistics. Their work was complicated by the refusal of several city officials to participate, such as the Police Commissioner, Louis Valentine.

One hundred and sixty witnesses testified at the twenty-one public and four closed hearings. The Commission invited “persons representing all stratas of the population of Harlem. Anyone who had a complaint against any public official… any laborer at the most menial occupation, etc.”

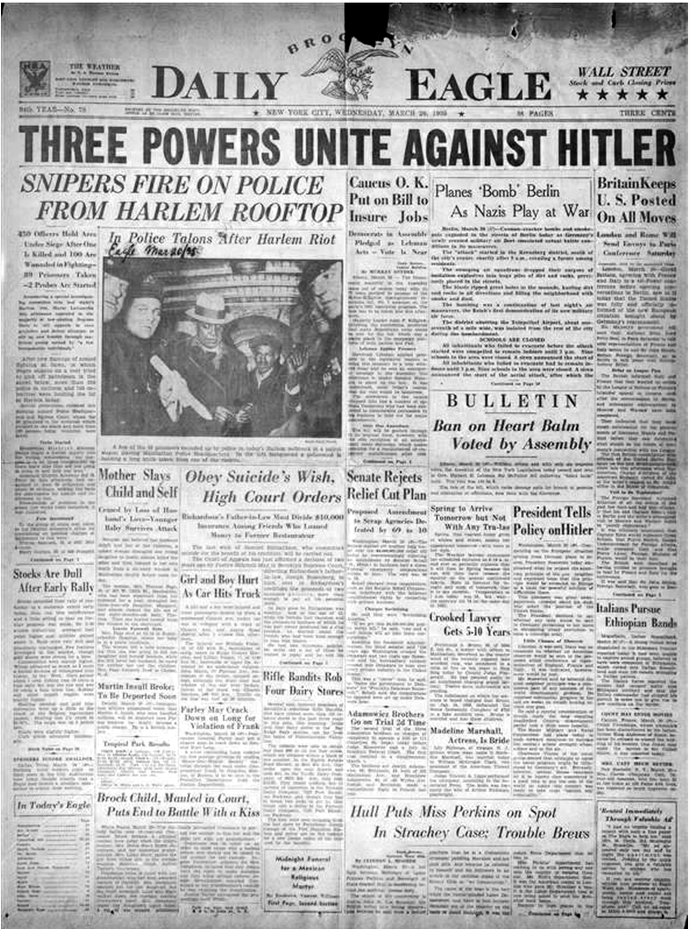

Chapter 1 | The Events of March 19th

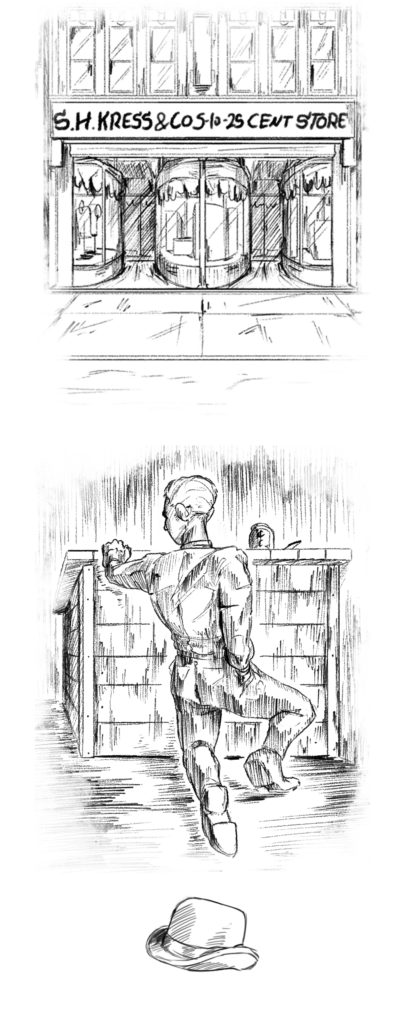

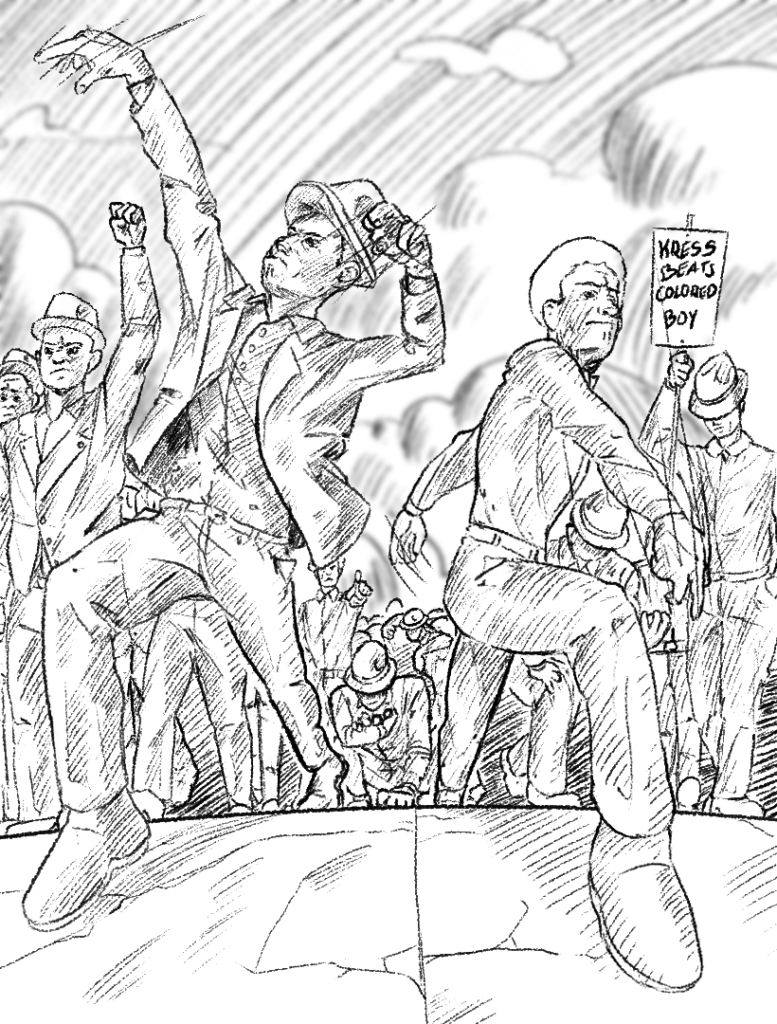

On March 19th, 1935, a young man, Lino Rivera, attempted to swipe a small penknife from the Kress store on 125th Street in Harlem. Store personnel intercepted him, took the knife away and “threatened him with punishment.” He bit them. They marched Rivera to the front of the store and called to a mounted police officer who brought him back into the store for questioning. Store management said they would not press charges and sent Rivera away through the back entrance to the store.

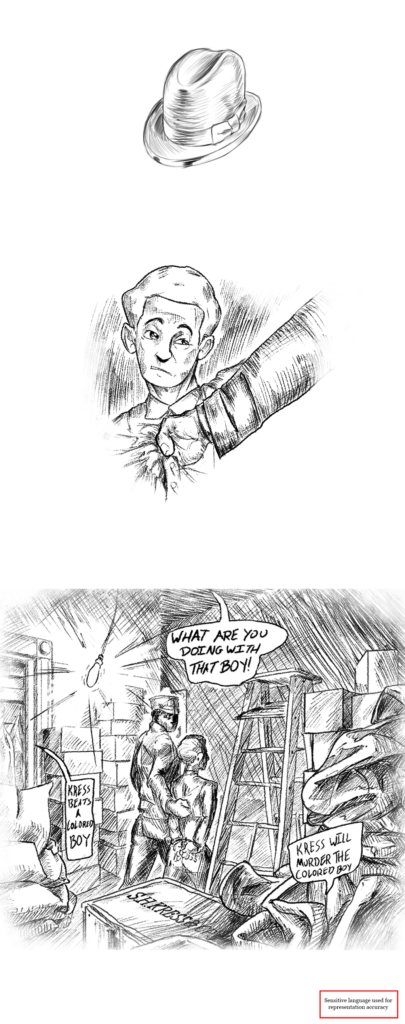

However, rumors that he was taken to the basement to be beaten circulated among shoppers. The appearance of an ambulance seemed to support that rumor. The ambulance personnel were there to treat the bitten store manager and they left without picking up a patient. The rumors escalated—claiming Rivera was dead. The driver of a hearse parked in front of the store went in to see his brother-in-law, unaware of the situation inside the store. Tension grew.

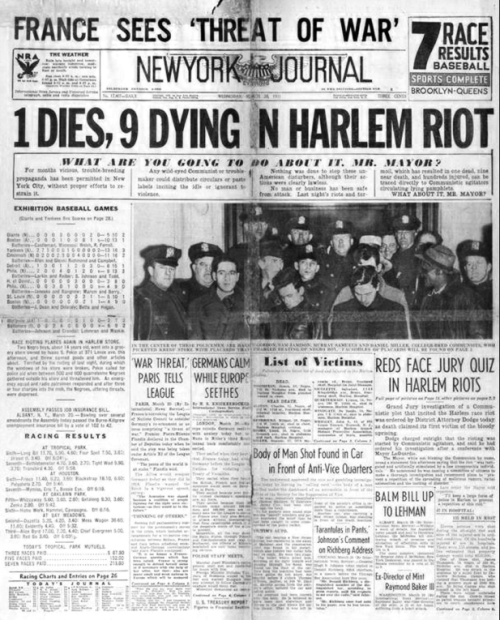

Police officers attempted to calm people by asserting that Rivera had been let go, unharmed. When the crowd persisted, the police officers told them to leave the store, that this was none of their business, which infuriated the shoppers. The store closed early, at 5:30, and the shoppers were hustled out. On the streets, they repeated that the young man had been killed. “With incredible swiftness, the feelings and attitudes of the outraged crowd of shoppers was communicated to those on 125th Street and soon all of Harlem was repeating the rumor that a Negro boy had been murdered in the basement of Kress’s store.”[1]

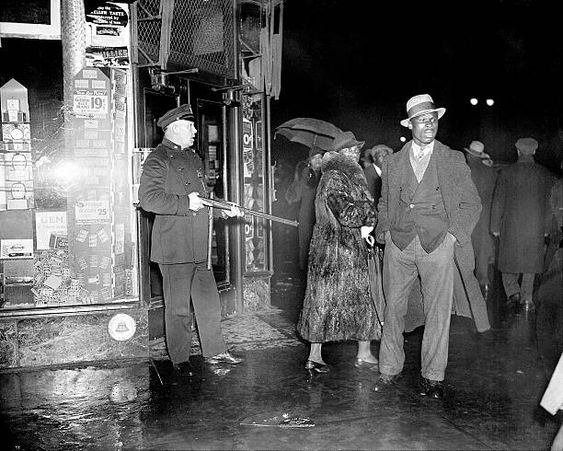

Street corner speakers tried to start a public meeting. The police ordered them to move from the corner. The speakers set up outside of the store. The police arrested the speakers. A store window was shattered. The police attempted to disperse the crowd, but they reassembled in other places. “These actions on the part of the police only tended to arouse resentment in the crowd which was increasing all the time along 125th Street. From 125th Street the crowds spread to Seventh Avenue and Lenox Avenue and the smashing of windows and looting of shops gathered momentum as the evening and the night came on.”[2]

“Lack of confidence in the police and even hostility towards these representatives of the law were evident at every stage of the “riot.” This attitude of the people of Harlem has been built up over many years of experience with the police in this section. During the early stages of the excitement in the store when there was still time for the police to prevent the spread of the rumor, they assumed, according to reliable witnesses, the attitude which is reputed to be their general attitude towards the citizens of the Harlem community.”[3]

At 7:30, a local civil-rights organization, The Young Liberators, and the Young Communist League both leafletted the area, further spreading the rumor and criticizing the police. Clusters of people gathered, the police dispersed them; they gathered again in front of other buildings. Windows were shattered and merchandise was looted.

This continued throughout the evening, into the early morning hours. In the midst of this, two young Black brothers returned home to Harlem after seeing a movie. Walking along 7th Avenue, they stopped at 128th Street. A crowd had gathered in front of a car accessories store while merchandise was being stolen. A police car arrived, and an officer emerged holding a gun. The crowd began running. The officer fired the gun and hit Lloyd Hobbs, a 16 year old. Hobbs died at Harlem Hospital a few days later.

The officer claimed Hobbs was looting items. Every other witness told a different story. After extensive interviews the commission concluded the shooting was unwarranted. “The shooting of Lloyd Hobbs, a boy having a good record both in school and in the community and being a member of a family of good standing and character, has left the impression upon the community that the life of a Negro is of little value in the eyes of the police. The circumstances surrounding this case exclude the excuse that the policeman was dealing with a dangerous criminal who threatened the safety and welfare of the community.”[4]

Artist’s representation of the events at the store, protests and police response.

Footnotes

[1] The Negro in Harlem, p.2

[2] Ibid, p.3

[3] Ibid, p.7

[4] Ibid, p.10

[5] Ibid, p.11